Barkhiz o Biaa, Saaqi: Lotfi II

This one will be a little different.

More than once here -- try this one on for size, -- I've said something like:

I have a whole series of literary "portraits" in mind, the centerpieces of which study I envision being Persian musical Masters like Mohammad Reza Lotfi.

And, wouldn't you know it? I've started to speak, and write, and paint them into being, since first conceiving them in thought.

You might want to read what I linked to above first, and, having stimulated your salivary glands with it, un-notch your belt a bit, then have a taste, preferably a slow and loving one, of this.

What that is, is a portrait of a man whom I consider not just a master of improvised Persian dastgaah music, but -- well, someone at whose feet I sit and learn many things.

I'm saying, he's as much my Master as any other.

The bond of blood is questionable, in the narrow sense, though doubtless in the broader; but I do declare him a spiritual father in more than mere name, which indeed we share.

I said this one will be a little different; it will.

I also said elsewhere that, for Lotfi, I "might even need to do a 'study' ... painting not one portrait, but many -- so much do I have to say about him, or so much depth and meaning does his image afford to the creative imagination that wishes to render it in art."

This is another in that series.

And, what it is is a review of a recording of his I found a few months ago, called "Gerye-ye Beid," which I'm told means weeping willow.

Please don't call it musical criticism -- that's obscene.

Here, we are aasheghs drunk on the same wine -- arms around each other's neck, stumbling out from the tavern door: you sing one line, I sing the next, and so we go singing a half-remembered song heard by the fireplace, far on into the starry night.

I remember the professor I talked about here.

I told you elsewhere that there was a time when, especially for teachers and professors, I could be "an indigestible little motivating factor for the engendering of sore tummies and poor sleep," while for the professor I'm talking about here, while maybe I wasn't quite that, I was the willful motivating factor for a twitchy eye, which later I did regret, of course.

Not that we were unfriendly, or that there wasn't a shared love and understanding -- so rare in the academic world!

No; despite her righteousness and genuine enthusiasm, I just think that, after all, she was trying to sell out without selling out (always a dangerous proposition), and -- like Marge Simpson trying to ingratiate herself with the country-club set by means of a thrift-store Chanel suit that she kept re-tailoring till it collapsed into a pile of threads and shreds, -- well, in the end, she didn't have that much of the genuine article left over to work with.

To be clearer: at the start of one of the two classes I took with her, I hit her with a left hook she didn't see coming.

I mean, with an essay I gave her.

She returned that left hook with a puddle of red ink -- I think I broke her nose, -- and made some shrill protestations about its unreadability.

I think she just wasn't used to being challenged, or stung.

Later, I jabbed her with this in one of the weekly "forum-posts" all the students had to do, of course for everyone to see:

"The Plaint of Nature," among other things, sets out a vision of the creation and continual regeneration of man, by God and through the directed assistance of Nature and her helpers. Its aim in so doing seems to be to argue for a certain natural, harmonious, lawful order in the reproduction of the human species in particular: specifically, by means of a heterosexual, married, loving relationship.

Alain does this by means of sentences that would never cut it in an English essay, and with all the sublimated sexual fervor of a perpetually chaste shut-in. Let's see if I can bring the general claim down to earth a little, before looking at a metaphor he uses to explain the various roles of God, Nature, and Venus in that process.

I underlined the jab, if your eye isn't hip to the sweet science.

Here's an example of what I'm talking about:

"But since for the production of progeny the rule of marital coition, with its lawful embraces, was to connect things unlike in their opposition of sexes, I, to the end that in her connections she should observe the orthodox constructions of grammatical art, and that the nobility of her work should not mar its glory by ignorance of any branch of knowledge, taught her, as a pupil worthy to be taught, by friendly precepts under my guiding discipline, what rules of the grammatical art she should admit in her skillful connections and constructions, and what she should exclude as irregular and not redeemed by any justifying figure. "

At the time, I actually copy-pasted that paragraph and saved it in a document for myself (so handy to this moment now).

I titled that document, "MY Writing Stinks?"

So -- you're having us read that, like this dude is some sort of expert on something -- certainly not clarity, -- and you're gonna bust my balls?

GTF out of here.

What I wrote (and haven't shared here) [Edit: I changed my mind] was pellucid, and had none of the stink of un-septically bottled sexual fervor that Monsieur Alain's prose had.

What he grew, if we want to think of it as a tree, still stank of the bog-water that fed its roots, while what I grew had only the fragrance of flowers.

Anyway, not to toot my own horn too much -- I'm going for jokes, not poses.

What I'm saying is, one day, this professor was trying to persuade me to write "within the grammatical constraints," so to speak, of that thieves'-cant they call proper academic expression, or some such nonsense.

She said, Then, if you like, you can write music-review articles or something like that on the side, and be as free and flowery there as you like.

I think she protested-eth overmuch, and spake chiefly of her own uneasy conscience.

Stung again by the gainbite of inwit.

So, what I'm saying is -- this ain't one of those music reviews.

I always use the same voice, even when I use different voices.

And, at the same time, on that same note, I'm put in mind of Frank Zappa (another idol with feet of clay, lying broken in the wastes of history):

"Definition of rock journalism: People who can't write, doing interviews with people who can't think, in order to prepare articles for people who can't read ...

"There are several reasons why my music has never really been 'explained' in the press. For one thing, the people who write the articles don't really care how it works or why it works ...

"Also, in those instances where the writer might actually care, his editor, convinced that the public doesn't care, will either cut or modify the article.

"The manner in which Americans 'consume' music has a lot to do with leaving it on their coffee tables, or using it as wall-paper for their lifestyles, like the score of a movie -- it's consumed that way without any regard for how or why it's made. Then, when it's merchandised, the emphasis shifts to the pseudo-personality of the artist."

Old gray mare ain't what she used to be, but -- well, Zappa still had some clever, or insightful, or incisive, things to say from time to time, and I can't help but remember them.

But -- well, we're not doing that kind of journalism here, or that other kind; in fact, let's not poison this whole enterprise with those words, or Zappa's.

Remember what I said:

Please don't call it musical criticism -- that's obscene.

Here, we are aasheghs drunk on the same wine -- arms around each other's neck, stumbling out from the tavern door: You sing one line, I sing the next, and so we go singing a half-remembered song heard by the fireplace, far on into the starry night.

Yes.

Someone said that the symbolism of bathing in the Ganges, as perfect absolution of sin, was a beautiful symbol.

Why?

Because sin is like dust -- it never stains your soul, not really, and washes right off, like dust from a weary traveler's skin.

Barkhiz o Biaa, Saaqi! Bring me a bowl of that Ganges-water!

In the name of the God of Soul and Mind -- for what can we invoke higher than this?

Let's talk about Lotfi.

Gerye-ye Beid.

Weeping Willow.

Elsewhere, I mentioned an older English gentleman, a client of the Spring Forest Qigong healing center, who I got to know over the course of a few phone calls, a lot of emails, and -- toward the end -- a few of his uncensored journal entries.

I mentioned that I'd shared not just that improvisation of Ahmad Ebadi's with him, but a few other masterpieces of improvised (and some not-improvised) Persian dastgaah music.

I was amused by his bemusement, but -- as I said -- I was also slowly opening him up to it.

Toward the end of my time at the healing center, when this gentleman shared his journal entries with me (which journal he said was where he sorted things out, but which I said seemed rather to be the space in which he explored his intuition), I shared Lotfi's Gerye-ye Beid with him.

He and his wife were a sweet couple.

She, mainly, was the one who came to Spring Forest Qigong for the healing, and it seemed to them both, if in different ways, that she wasn't making any progress.

One day, not long before this and after their daughter had gotten married, the gentleman shared a wedding-photo with me.

The bride and groom were in it, of course, and so were he (the gentleman I keep calling a "gentleman") and his wife.

I'd heard her voice before, as I had heard the daughter's, when once they all came on the phone line to say hi to me; and, I have to say, I think I fell in love with both the women, right then and there!

They were beautiful -- I'm telling you as someone who listens to beautiful music all the time.

But in this picture, the wedding-photo, what I saw in the wife, the mom -- was that she had some deep, deep sorrow, some pain that haunted her eyes.

She had a lot of other health challenges that I knew about, given my conversations with her husband and the nature of my work at the healing center -- but I'd never heard mention of this thing I saw.

And yet I knew, and told the gentleman-husband -- I don't know what that's about, but whatever it is, that's where the healing work is, and until that's healed, you're both just beating around the bush.

I said it much nicer, of course, and -- since my audience in this gentleman was a musician with a sensitive ear -- with a bit of poetry.

I didn't hear from him again for a few weeks after that.

"Slow is the experience of all deep wells -- long must they wait to know what fell into them."

When he finally wrote back, explaining and apologizing, I told him he didn't have to say anything -- that what he not-says is as meaningful as what he says -- as meaningful as the silences between musical notes.

Anyway, he said he'd told his wife what I'd said about her deep and hidden pain, and that that had not only "struck a chord" with her -- but had made to flow an overfull well of tears.

There's more to this story, and it's -- well, it's very sad, and very beautiful, and full of the mystery of healing that, so often, I and many others have been witness to in the kind of work Spring Forest Qigong does.

What I'm trying to say is, not long after this drawing from the overfull well, so to speak, I shared Gerye-ye Beid with the gentleman, and to my surprise -- both he and his wife listened to it.

He gave me something of a review in return -- or, rather, a recounting of the flow of associations engendered in him by the music and a reflection on the data crystallized in him by the impressions it made upon his second being-body, as Gurdjieff might have said.

That kind of music speaks through and to the heart with a sure science, being the Objective Art that it is; so, though what impression that makes on a person depends on that person's level of spiritual development, itself determined by what conscious labors and intentional sufferings he's undertaken and undergone -- the impression of that kind of art, and music, always has the same flavor.

And, what I'm saying is, this gentleman's impressions were spot-on.

I wish I had them to share with you, but I don't.

I shared my own impressions with him in return, as well as a higher-level explanation of Gerye-ye Beid, such as I was able to offer.

I wish I had that to share with you, but I don't.

And, I won't try to recreate it.

"The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on."

But here's what I'd like to tell you.

The gentleman said he and his wife were drawn into the performance from the first, and when Lotfi's voice finally came in -- I got chills just now -- it was like a moment of revelation to them.

The voice isn't "beautiful," but it is perfect.

"Ah! -- that, indeed, IS the voice that makes that music!"

I didn't write this to him, but this is what I wanted to tell the gentleman -- who loved to make music, but always seemed just to fiddle and jam with it, going on in endless circles.

This is what I wanted to tell him, who seemed to stand silent, wringing his hands in sorrow as his wife (herself aforetime a mesmerizing singer, I was told), held him captive with her suffering.

I'd never have told him this when I worked at Spring Forest Qigong -- not when I worked there, not in that capacity.

Don't worry about her. Stop trying to help her -- you've tried enough. Put everything, and I mean EVERYTHING, into your music. Go into your room, shut the door, and play that guitar from sun-up to sun-down, and then some, and let her stand outside the door and listen to what you have to say. Maybe that's what she needs to hear, and maybe that's what she wants to hear. Maybe that's the healing she needs, and the healing you can give her.

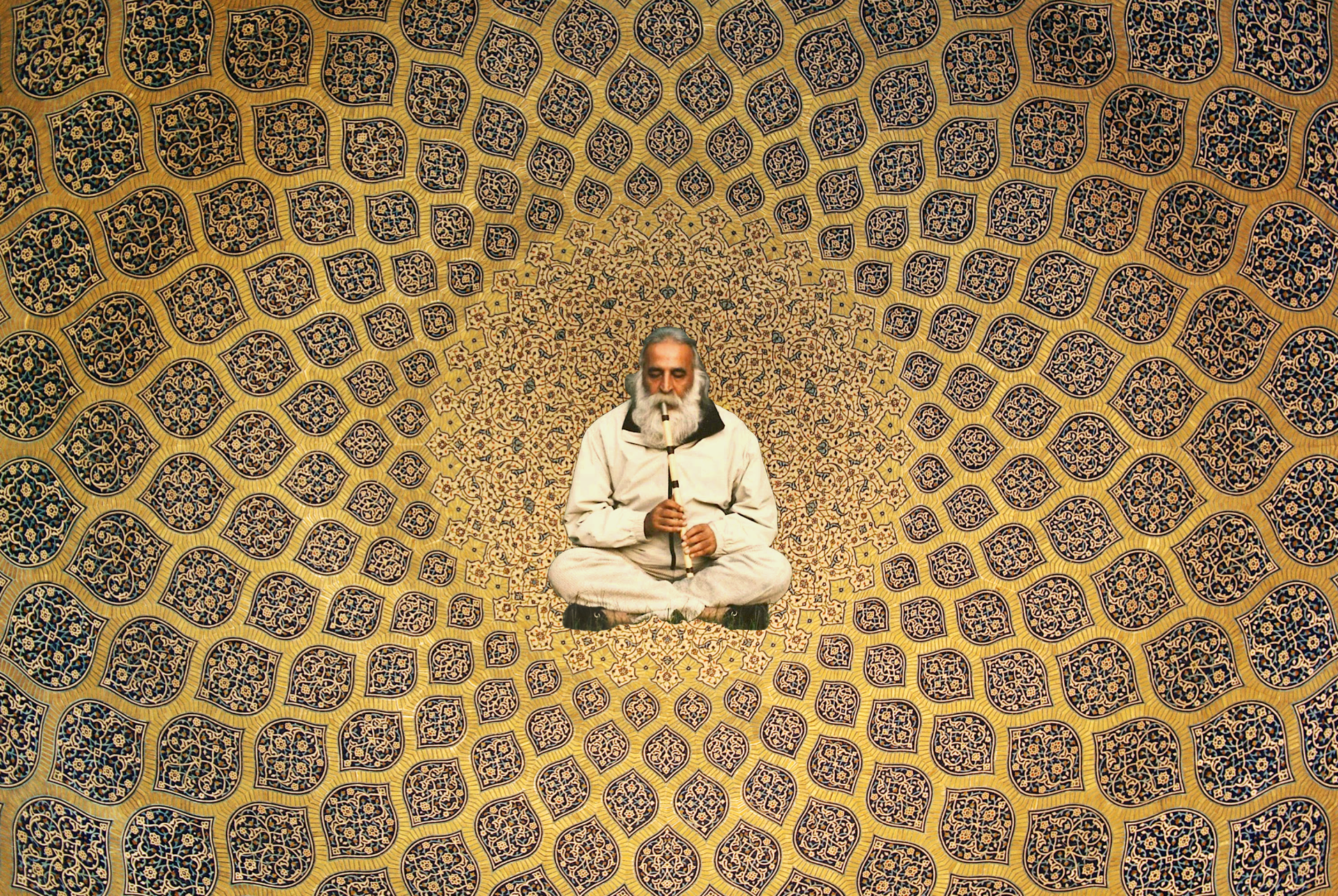

What I'm saying is -- that's what Lotfi did with that performance.

In fact, that's what he did with all his performances.

Just this year, someone made a retrospective on Lotfi's life, interviewing some of his students and fellow musicians. They all speak of him with reverence, and not infrequently with tears.

One student, in particular, told of a live performance of Lotfi's, broadcast on the radio in the US, that he was witness to -- sitting there, right by his side.

It's a beautiful story.

But the point is, coming to the hotel just before, they'd had a chance-encounter with a stranger in the lobby, and the energy of that encounter changed the course of what, and how, Lotfi would play for the performance-to-come.

Anyway.

When he was done playing, Lotfi's student -- the one telling the story -- was awestruck, silent, and -- then he just started crying and crying.

Lotfi said nothing, but got up, hugged him, caressed his back, and as his student wept and wept into his shoulder, said:

"Remember this feeling."

In that same retrospective, another student said, Lotfi always told us, No matter what happens in your life, anything at all, anything that you feel -- pick up your instrument and play it.

How do you think he was able to move people with what he played?

He had first brought everything he had ever felt to the taar and setaar, sitting alone in his empty room with the door shut.

Mmm.

I had so much more to tell you about this performance, Weeping Willow.

I think I've already said what needed to be said.

But since, after tears, sometimes it's good to have a little light talk -- why don't we do that?

I think Weeping Willow is called that, because that's exactly what it sounds like.

Only someone who'd first felt all the feelings of a weeping willow and then put them into his setaar could do that.

And, one more thing -- what I did tell that gentleman was this.

That performance in particular, and that kind of music in general, is a very Iranian way of praying.

You may not have considered it prayer before, but I do.

I hear this again and again in the masterpieces of the masters of Persian improvisational dastgaah music.

It's music of love and longing.

You may think it's about men and women, but it's not; it's about the soul and God, speaking the language of men and women, because that's about as close as language, and earthly experience as-yet-unwarmed by the light of divine passion and compassion, gets to explaining it.

In this prayer, the one who prays feels the pain of separation, the unquenchable longing for release from suffering and for the love of God.

So -- he laments.

The lamentation starts soft, builds, and reaches a peak. From that peak, standing on the precipice, the one who prays might shout, but usually he sounds a cry from the heart -- Why, God? Where ARE you?

He stands a moment in the silence of that cold peak, hears no response, and starts to walk back down -- a little sad, a little empty.

Rumi said:

"The cloud weeps, and then the garden sprouts.

The baby cries, and the mother's milk flows.

The nurse of creation has said, Let them cry a lot.

This rain-weeping and sun-burning twine together

to make us grow. Keep your intelligence white-hot

and your grief glistening, so your life will stay fresh.

Cry easily like a little child."

Those who cry from the heart like that speak to God with a sure science; he will always speak back.

As the one who prays walks slowly back down the mountain, suddenly he hears something -- so soft, so sweet, he wonders if he's imagined it.

But, no!

It's getting louder, sweeter, clearer; and, when he realizes what it is, his heart swells to bursting, his mind is burned to ashes in the rising fire of his heart, and -- he begins to dance in its ashes.

The dance of a fool, a drunkard, a madman -- and, yet, with an inner rhythm and a solemn grace.

Now, God is dancing him.

What is left but to cry with joy, to praise God, to praise the Master who led you to him?

And, in the end, when that spirit leaves the one who prays, as it always does, the silence of the mountain returns, not with a cloud this time, but with the softer darkness of night, he slowly walks his way all the way down the mountain.

Gerye-ye Beid.

15 April 2022

Those who only dip their toes will never touch the depths.

Champion Toe-Dipper

Signs and wonders!

Well, wouldja you look at that -- you actually emailed me. I'm glad you figured my website out.

If you would, give me a little time to reply, ok?

I'll do my best to reply quickly. If you don't hear back within a couple days, you may want to write again.

Take care,

Jian

Oh, boy.

Gremlin in the machine. I don't think your message went through.

Why not take a constitutional and try again a bit after, huh?

Jian