Salve, Magister!

Well.

Here I intone again, a full month later and more, the refrain I first sounded here.

That is:

"You may not have noticed, but it's been a while since I've written."

What can I say?

I've had other stuff going on.

Let's hope that the complexity of the melodic themes I weave here for you (and for me) is such that, as they continue to unfold, that refrain returns only rarely, emerging amid the themes' endless undulations only when least looked-for and as an "ingression of novelty," say on the order of a pink dolphin breaking the sea's surface to wink at a lonely fisherman before slipping unseen back into the depths.

I had to pause and read that sentence a few times. Maybe you did, too?

Near as I can tell, the grammar checks out, so -- that ain't it.

No.

As I read (and wrote) the sentence, an image crossed my mind.

I can't remember if it was from a Bugs Bunny cartoon, or from The Beverly Hillbillies, or else if it's proper to my own, in some respects, cartoonish inner imaginal realm, a gas-like emanation arising from my subconscious mind, overturning my wits and loosing my tongue like the subterranean "pneumatic inspiration" of the Delphic oracle.

Take a couple huffs of THAT heady stream of hot air before going on for "optimal effect," why dontcha?

Anyway.

The image was of some dirty-faced street-urchin crank-starting a rickety Model-T with patched-up, overfull tires. Lots and lots of winding, lots of sputtering and coughing and grumbling from the car... followed by a cloud of black smoke and something approximating a hum from the engine.

Yes.

I believe I mentioned here "having established a well at the inexhaustible source."

Well, that's true.

But, let's say... having been away a while, my hands are less steady in the drawing than once they were.

Let me take a step back.

Speaking of complexity of melodic themes, of course I had this in mind:

"[A]nd behold! a third theme grew amid the confusion, and it was unlike the others. For it seemed at first soft and sweet, a mere rippling of gentle sounds in delicate melodies; but it could not be quenched, and it took to itself power and profundity. And it seemed at last that there were two musics progressing at one time before the seat of Ilúvatar, and they were utterly at variance. The one was deep and wide and beautiful, but slow and blended with an immeasurable sorrow, from which its beauty chiefly came. The other had now achieved a unity of its own; but it was loud, and vain, and endlessly repeated; and it had little harmony, but rather a clamorous unison as of many trumpets braying upon a few notes. And it essayed to drown the other music by the violence of its voice, but it seemed that its most triumphant notes were taken by the other and woven into its own solemn pattern."

That is, of course, from Tolkien's Silmarillion -- I finally had to get another copy, and did, and read it again, for maybe the third or fourth time.

This was after reading Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit again, again for maybe the third or fourth time, all in the last couple months.

It's crossed my mind to write something about Tolkien, but... not yet. Still gestating.

And, speaking of ingressions of novelty, of course I had in mind Terence McKenna's Invisible Landscape and his so-called "Timewave Zero."

Both Tolkien and McKenna were big, big influences on me in my 20s, if in very different ways.

Both have left their indelible energetic impressions on my mind and spirit, but, 15 or 20 years later, I have to say in echo of a greater voice than mine, "whatsoever ye have spoken in darkness shall be heard in the light; and that which ye have spoken in the ear in closets shall be proclaimed upon the housetops."

What I'm saying is...

Tolkien's influence was like the "third theme of Ilúvatar" -- sweet and self-effacing, but ultimately irresistible in its power, while McKenna's influence was like Melkor's endless braying of one note upon many trumpets -- dazzling at first, but ultimately... empty.

Why am I saying this?

Elsewhere, I've talked about my time at the University of Maryland -- most relevant to the topic today, here and here.

There's your context for the day.

I mentioned writing an essay for a professor that I liked, but who I also decided to give a little intellectual indigestion.

I also mentioned wondering whether to share that essay with you; in the end, I've decided to do just that. That essay is below.

Anyway, all I'm saying is... it's not the best essay, both because my craft has continued to improve (though I wouldn't say today's effort is the best evidence of that -- forgive the sputtering and reek of my crank-started Model T) and because the subject-matter didn't particularly interest me.

And, what I'm also saying is -- the essay begins with reference to Terence McKenna.

Again, what I'm trying to say is... having re-immersed myself in Tolkien's creative work and his imaginal realm, what I see in him now is a man of pure heart and sincere intentions who, over the course of a long life full of many obligations and always guided by his love of creation and discovery, stole many moments to shape and elaborate and reflect upon... well, what I think is one of the most beautiful, rich, broad, and deep "sub-created" worlds ever brought into being.

As I go deeper into my own inner realm and live longer in this "outer" created one, the light of Tolkien's truth shines ever brighter and illuminates ever more in my eyes.

McKenna does not do that; and I'll leave it at that.

Or, rather, I'll leave it at this -- there's light and then there's light, as the light of God and the light of Lucifer.

Yet, a few things McKenna said, here and there, still have a little shine on them that's not entirely unlovely, or unwholesome.

The essay that follows was written when my eyes were still more dazzled by that shine; and because without those words, that essay would not have come into being, I at least owe them, and McKenna, some small gratitude.

Without intending to impute to my own sub-creative endeavors the profundity of God's Supernal Theme of Creation, I will say that McKenna's most triumphant notes were taken by me and woven into my own solemn pattern.

Here you go.

25 July 2022

"Freeing the Fragrance of the Mystic Rose"

25 February 2013

Has the eye ever misbelieved its seeing -- not what it sees, but that it sees? It would be a strange phenomenon. Terence McKenna said,

We're born into what William James calls a “blooming, buzzing confusion,” but by the acquisition of words we mosaic over various sectors of this blooming, buzzing confusion... We replace the unknown with the known through... a cultural mosaic of words that is interposed between [us] and reality. Reality... is only an unconfirmed rumor brought through the medium of language...

[I]magine an infant lying in its cradle, and the window is open. And into the room comes something, marvelous, mysterious, glittering, shedding light of many colors; movement, sound, a transformative hierophany of integrated perception. And the child is enthralled, and then the mother comes into the room and she says to the child, “That's a bird, baby, that's a bird.” Instantly the complex wave of the angel-peacock-iridescent-transformative-mystery is collapsed, into the word. All mystery is gone... (“Ordinary Language”)

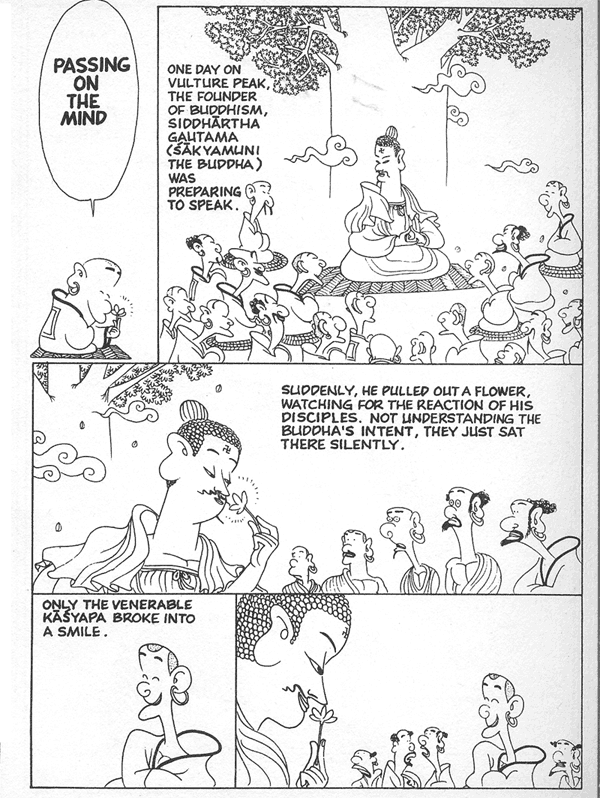

Just as strange would it be for the speaking tongue to misbelieve its saying, so deeply are we immersed in the world of words, even as we are in the world of our senses. But if we are to accept McKenna's observation, then it seems that with all words, even the best, one can only talk about -- "on the outside of" -- but never truly say. Knowing this, the East has called enlightened not those who have perfected the intellect, but those whose intellect, whose mind and whose language, has dropped away, leaving only silence, preserving unmediated and intact the original mystery of perception. Knowing this, the transmitters of esoteric and mystical understanding have always spoken by not speaking: they have used parable, silence, gesture, posture, color, and image to convey their truth. The pointing finger says more than the pointed quill.

In the late twelfth century, Marie de France left the world several lays, poetic romances dealing chiefly with what is called "courtly love," its consequences, and its complex interactions with bonds of feudal and marital loyalty. These lays, being short works which, however, were also concerned with the investigation of elaborate themes, therefore employed rich and subtle symbolism, which served in a condensed and direct manner to transmit to the reader a message which, very often, served both as a complement to and a crystallization of the message which the rest of the story addressed at length and more conventionally. This short paper, therefore, will consider a symbolic episode in one of Marie's lays in particular, arguing that it not only serves, at the story's climax, as a solution for and a response to the chaos of concerns and entanglements of loyalty in the story, but that it does so in a direct, concentrated manner that bypasses the more logical part of the mind, the better to convey Marie's essential message to the understanding.

In "Eliduc" we have the longest and most complex of Marie's lays; as such, and, occupying, as the last in the sequence of its companion-stories, a place that inherently heightens any thematic or moral issues, it may be said to provide a definitive answer to all the questions and concerns that precede it, the very broadest conception of which I have given above. We must, therefore, expect any symbolic episode in such a place to have an especially deep and rich signification. But to come to an understanding, either of the story or of the signification, a short summary of the plot must be given.

Eliduc was an ideal and chivalrous knight, married to an ideal and noble wife, Guildelüec; between them was a great and loyal love. One day Eliduc, banished by his lord because of jealous slander, leaves Brittany to seek paid military service elsewhere, but not before pledging fidelity to his wife. Coming to Logria, he delivers a besieged, heirless king from his enemies; in return, Eliduc wins renown, wealth, and custody of the land, promising service to the king for a year. The king's daughter, Guilliadun, however, falls in love with Eliduc -- and he with her, if after much struggle and self-questioning. Following a plea for help from his lord in Brittany, Eliduc returns to save him by his military might, both leaving Logria without fulfilling the term of his service and pledging marriage to Guilliadun.

Having saved the king in Brittany, Eliduc returns to Logria, takes Guilliadun away from her father by night, and sails homeward with her; but while they are at sea a storm arises, which the men take as divine punishment for Eliduc's adultery. Hearing the truth, Guilliadun swoons, Eliduc thinks her dead, and, when they come to land, he places her on an altar in a hermit's chapel, vowing to become a monk upon her burial. For days, Eliduc visits Guilliadun, until Guildelüec, suspicious, comes with the help of a servant to the chapel, finds her rival and, seeing her great beauty, forgives Eliduc, revives her, dissolves the marriage so the two lovers may wed, and herself becomes a nun. Eliduc and Guilliadun live happily together, until in old age Guilliadun joins Guildelüec as a nun, Eliduc builds a church which he endows with most of his wealth, and he himself becomes a monk.

This summary is only to place the symbolic episode, much- and indirectly alluded to above, in a meaningful context; what it does not do that Marie's telling does, however, is provide the reader with a clear thematic and emotional center of gravity, around which all the story's other events might revolve and find meaning. This center, I affirm, resides in the brief episode with the weasels, recounted here at last.

Guildelüec, having just discovered Guilliadun and understood her husband's love for the girl, sits weeping and lamenting her, when:

a weasel, which had come out from beneath the altar, ran past, and the servant struck it because it passed over the body. He killed it with a stick and threw it on the floor. It did not take long for another to run up which, seeing the first one lying there, walked around its head, touching it often with its foot. Unable to rouse its partner, it seemed distressed and left the chapel, going into the woods in search of herbs. With its teeth the weasel picked a flower, bright red in colour, and then quickly returned, placing it in the mouth of its companion, whom the servant had killed, with the result that it quickly recovered (Burgess 124).

Thereupon, Guildelüec has her servant strike the second weasel, causing it to drop the flower, which she then, in imitation of what she saw, places in Guilliadun's mouth to revive her. Thenceforward, all of the story's problems are resolved, and, of course, everyone lives happily ever after, after a fashion.

What is the reader to make of this very curious manner of resolution, and of the manner of happiness that the three main characters find in the end as a result of it? The editors of the lay set us in the right direction: "[I]t could well be that we should take both weasels to be female... T.S. Duncan points out that the weasel 'may have been generally thought of as a female animal,'" while in "folklore the weasel is credited with knowledge of the herb of life. The red flower... is probably symbolic of the flow of blood and the restoration of life to the dead girl" (Burgess 128). But this is toe-dipping, and only diving headfirst gets one deep, whether in water or speculative interpretation.

We have seen that Guilliadun is laid out on an altar in the chapel of a "holy, saintly hermit" (Burgess 122). Both of the weasels may be taken to female, while the flower the one uses to restore the other is symbolic of blood and life; the flower is put in the mouth of the afflicted. The first word Guilliadun says upon awakening is "God," whereupon Guildelüec's first words are of thanksgiving to God. Guildelüec, who is the keenest interpreter of ambiguities -- whether her husband's changed behavior after his adultery, or the weasel's response to its partner's death, -- immediately renounces her marriage and turns to religion, while in the end, even after the fulfillment of their desires and a long, blissful life together, both Eliduc and Guilliadun also turn to religion.

What all this suggests is quite clear. The story, prior to the episode with the weasels, is characterized by chaos amid an entanglement of earthly loyalties; indeed, all of the stories preceding "Eliduc," whether ending in bliss or misery, showed something of loyalties placed in opposition, loss of identity, and suffering arising as a consequence of love. Here Eliduc is betrayed by his lord, then pledges loyalty to a new one. He pledges loyalty to his wife, then betrays it; then, betraying his new lord, he returns to the old. In taking Guilliadun away by night, he betrays the king of Logria again, and Guilliadun herself by failing to tell her of his prior marriage. All of this comes to a climax when Guildelüec discovers Guilliadun -- and what happens? She receives the answer for salvation from the woes of earthly love and entanglement in secular bonds: the resurrecting blood of Christ, and withdrawal from the world for the contemplation of God. That is higher than even the highest earthly bliss, and the only lasting source of happiness.

Notice that Guilliadun is "dead" -- not just physically, but spiritually: she lives yet in the world of earthly love. The flower is red, like blood; Christ, as redeemer of man fallen in sin, is said to have paid the price for man's redemption from earthly guilt with his blood, and it is his flesh and blood that Christians understand themselves to be eating, in imitation of an episode in the Bible, as a sacrament. In that regard, the placing of the red flower in the mouth of the dead is symbolic of the administering of the Eucharist, also known as the Sacrament of the Altar; in light of this, it is clear why both women's first words after the resurrection should be addressed to God. Furthermore, a flower is conventionally taken as being the peak and the culmination of a plant's growth, a literally superior, supernal manifestation of a slow, unlovely process begun inferior, in the earth. And the two weasels correspond to the two women: the perceptive member of each pair gives "new life" to the other, through the "blood of life."

Granting this interpretation as valid, still the question arises: why convey the message in such a way, with weasels and roses? As I have suggested above, there is among those whose function it is to transmit profound mystical or esoteric understanding, a long tradition, not limited by place or culture, of transmitting such understanding through indirect means, which, paradoxically, has a more direct action on its recipient; I have argued both for the mystical-spiritual intent of the author, and for the specific Christian correspondences in the weasel-episode. Therefore it would be graceless, didactic, and diluting of its strength for Marie -- especially in the inherently suggestive medium of poetry -- to propound her salvific message explicitly and at longsome length. Nor, indeed, would the effect be so visceral and emotionally satisfying: only symbolism suffices. And consider Maurice Nicoll:

The idea behind all sacred writing is to convey a higher meaning than the literal words contain, the truth of which must be seen by Man internally. This higher, concealed, inner, or esoteric, meaning, cast in the words and sense-images of ordinary usage, can only be grasped by the understanding (2)...

Since all sacred writings contain both a literal and a psychological meaning they can fall in a double way on the mind. If Man were capable of no further development this would have no sense. It is just because he is capable of a further individual evolution that parables exist. The "sacred" idea of Man... is that he possesses an unused higher level of understanding and that his real development consists in reaching this higher possible level. So all sacred writings, as in the form of parables, have a double meaning designed to fall on the level of man as he is, and at the same time they can reach up to the higher level potentially present in him and awaiting him... This language -- the language of the parable, allegory and miracle -- is lost to the humanity of today (7).

Therefore one might say that Marie, in accord with this sacred idea of Man, is attempting, by means of symbolism, using the best means known to her, to serve for her audience as sun and sower alike; if we attend to her with our unused higher level of understanding, we, too, may be like the good earth on which the seed falls, yielding fruit that springs up and increases.

(From Zen Speaks)

-------------------------

Works Cited

Burgess, Glyn S., and Keith Busby, eds. The Lais of Marie de France. London: Penguin, 1986. Print.

McKenna, Terence. "Ordinary Language, Visible Language, and Virtual Reality." deoxy.org. n.p., n.d. Web. 25 February 2013.

Nicoll, Maurice. The New Man. New York: Penguin, 1967. Print.

T'sai, Chih-chung. Zen Speaks (Brian Bruya, Trans.). New York: Anchor Books, 1994. Print.

Not bad, huh?

As I re-read that essay before posting it here, I realized that appended to it was the "Honor Pledge."

Let me tell you about that really quick.

In Gettin Medieval, I said that, in those days when I waded waist-high in the muck of the Augean academic stables, I could be "'a thorn, or a stinging fly, or an indigestible little motivating factor for the engendering of sore tummies and poor sleep' to any professor with slack in their act."

There, too, and in Barkhiz o Biaa, I mentioned bloodying the nose and welling up the eyes, by means of well-timed literary jabs, of that UMD professor who, I assure you again, I liked well and who liked me in return.

The essay you just read was that, so to say, "opening salvo" in that friendly exchange.

"Salve, Magister," indeed!

As Rick James asked Charlie Murphy, "What did the five fingers say to the face?"

But what I haven't told you till now is that, on all the essays we wrote in both those classes with that professor -- namely, Chaucer and Medieval Literature, -- we were all required to write out the "Honor Pledge" and to sign and date it in pen.

I won't go on and on about it, because what I'll share below says everything.

But, what I will say is that, toward the end of the semester, when I met with the professor in her office (as all the students had been asked to, as sort of an "evaluation,") she brought up what I'd written -- what follows below.

By then she'd attuned herself to the swing of the tempo of my thought, as I had attuned myself to hers. So, she wasn't mad.

No.

But she told me that, in the English Department's recent faculty meeting, she'd brought up my conscientious objection to the Honor Pledge, that some of the faculty had "received it well," and that I was invited to come before them and "plead my case."

I think she was both pleased and impressed and was, so to say, opening the door for me to come in and "hold forth" before that august gathering of academic luminaries.

I laughed, of course, and told her -- You know, that's ok. I made my point, and after I graduate, I don't plan ever to come back to college again -- I've had enough already.

Thank God, I've kept my promise.

Here you go.

"The Honor Pledge is designed to encourage instructors and students to reflect upon the University's core institutional value of academic integrity. Professors who invite students to sign the Honor Pledge signify that there is an ethical component to teaching and learning. Students who write by hand and sign the Pledge affirm a sense of pride in the integrity of their work. The Pledge states:

[Edit: I can't seem to find the actual Pledge -- all I have is a copy of the essay, not the original, and I didn't write out the Pledge on my copy, nor sign it.]

I'm sorry, but this elevated language doesn't impress me: all it means is, "We don't trust you to be honest, you filthy little cheat, so we will twist your arm to sign these words so we can punish you all the more severely if you disguise someone else's words as your own."

I'm sorry that the University demands it.

To demand a pledge of non-cheating as a symbol or signifier of ethics in teaching and learning is a supreme insult to me, the learner, who have always learned first for pleasure and for the sake of understanding, with no thought of reward or gain -- especially insulting and hypocritical coming from an institution which, contrary to the ethical principles and practices of the most elevated teachers and lovers of wisdom, demands money for service (rubefacient meretriciousness), and seeks by metric and rubric to quantify worth and understanding.

But if the University feels safer when I write these words, then, to keep peace and satisfy the desire of the ardent masqueraders, I will write them for it, pitying it as I would someone "half-witted, ... timid as a lone woman with her silver spoons, [who does] not know [her] friends from [her] foes." What can an institution which, on principle and without cause, suspects others of an inclination toward dishonesty know about a "sense of pride and integrity"?