Pish-Dar-Aamad

(Matha)

Elsewhere (Many Masters, Many Mansions), I said I'd like to paint a series of portraits, "limning with words an accurate picture," as a Learnéd Preceptor of mine might have said it, of the Masters of Persian dastgaah music who had set fire to the field of reeds.

I'm not sure who will read this, or when; but as I write, I haven't yet painted those portraits, except as sketches in thought.

I will.

But before I do, I feel I've been commissioned by my Patron to place this portrait, and maybe one other, over the entrance to the temple hall.

One begins an endeavor with a prayer; the dar-aamad of the improvisation begins with a curtsy.

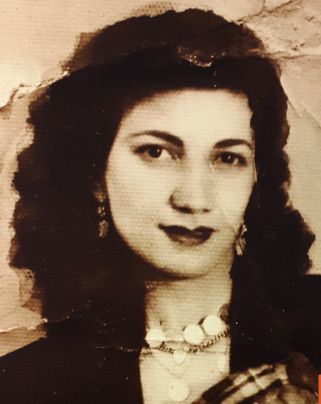

Rest your eyes, if you please, on this lovely mien, and then we'll get to what I mean:

That's my grandma, my father's mother.

You can't tell by reading this, but I took a long, long pause after saying that, just gazing into that face. Is it just me? That picture says a lot.

Her name was Eshrat.

To you, that may not sound beautiful; but I'm told it's an Arabic word, and in Arabic, it means pleasure, enjoyment.

Fitting for such a beauty, don't you think? But that's not all the picture says to me.

It's the eyes.

The more I look, the more I see. The face keeps changing, keeps telling me something different.

Incredible depth.

But, the thing is, I didn't know her as that young woman. I knew her as an old woman.

And, the thing is, I never really saw any depth in her.

Maybe this is getting ahead of myself, but I have to say that, as a tumultuous-hearted, static-headed teenager, I even hated her sometimes, scorning her simplicity.

To be honest, I even thought she was stupid.

It hurts to say that, but -- I've since learned better.

Back then, I might have said -- what depth could she possibly have?

I have gotten a little ahead of myself, so let me take you in a different direction -- a few different directions, actually -- to take you where we were going.

Just a series of freehand sketches for you, by the echo of whose impressions on your mind an image of other making than mine might arise in your heart.

Once, when I was maybe 8 or 9, we were sitting outside on a lovely summer morning -- on the front steps of my aunt, her daughter's, house.

She loved everyone, but she really loved me. I was her favorite.

She was barely literate, no education to speak of, but -- she could read her Holy Book and her prayers. That's all she ever read, until much later, when she decided she wanted to develop her ability to read and write, she would read and copy elementary-school primers.

That morning, she was teaching me prayers. She did that more than once. I don't know why I remember that, but I remember sitting there with her, not a care in the world, and having her say a line and have me repeat it, say a line, and have me repeat it.

Other times, she'd have me sit next to her on the sofa, with a sort of prayer-book primer, and have me read the words, sound them out one by one.

Years later, when I was maybe 18 or 20, we were sitting again on the front stairs of the house -- this time, my dad's house. There were lots of stairs at that first house, just a couple at this one.

For some reason, that day, she told me about her youth. I don't think I ever heard her talk about this with anyone else, or any other time.

Like I said -- she liked me the best.

Do you know what she told me one time?

This was in the days of tumult and static, of hatred and scorn, when surely I was full of filth and self-loathing.

She said -- Jian, to paaki. MAA gonaah-kaarim.

That is -- Jian, you're clean. WE'RE sinners -- or, you could translate that as, I'M a sinner.

Then she said, Pray for me.

I hated to hear that then; now, it makes me cry. I don't know who was purer than her. Who would pray for her?

I think of John addressing Jesus:

I have need to be baptized of thee, and comest thou to me?

At times, when I wonder how I would describe her to people who never met her, the phrase that keeps coming to me is, She didn't even know HOW to lie.

I mean, I don't know if she was capable of it. When she was angry with you, she was angry with you. When she loved you, she loved you. When she didn't know, she didn't hide it.

That's why everyone loved her -- she was exactly who she was, and it wasn't anything you felt was "better than you."

Which brings me back to the steps of my father's house.

She was one of, I think, 6 or 7 sisters, and she was one of the elder ones.

The ones before her had no education, the ones after her did (and were quite "successful" in that respect), and -- of course, she had no education, either.

That day, she told me she grew up on a farm, in the country. She said, at 16, her parents told her she was going to marry Lotfi.

I have pictures of him -- he was some sort of military guy, maybe an officer -- he looked very disciplined, very stern. No smiles. He was, I'm guessing, 30 or 35 years older than her.

That day, she told me -- I was 16. I didn't want to get married.

I don't remember everything else she said, but I remember how she said it. She wasn't angry, she wasn't sad. She was just reflecting on it after many years -- well, maybe with a tinge of anger and sadness.

But what I'm saying is -- she just accepted that that's what had happened.

So much of her life, that I saw, was like that.

Coming to stay with us in the US, for months or even years at a time as she often did, she was a stranger in a strange land.

My dad said once, She has no sense of history. She thinks they had cars in the time of George Washington.

She never learned English. She knew a few words -- aw-RANJ, gooWAsez, aPELL, tamTAM. That's orange, glasses, apple, Nintendo -- to give you a sense of her life, and mine, at the time.

Yet, I don't remember her ever seeming helpless.

I remember we took the Ride On bus a lot -- and she'd take it all over town by herself, after a while. If you don't know, these buses have, or had, a little... kiosk thing by the driver. On it, a listing of the rates -- some for seniors, some for kids, and so on -- and little slots for coins or dollar bills.

The rates were what they were.

Maybe, at that time, it was 50 cents or a dollar, depending on where you were going.

But she would love to come home (mostly, having visited the masjed, or the church, if that word makes more sense to you, or one of her kids or nephews or friends) --

-- and let me take a side-track by saying, all these people -- friends, family, church -- would always say, Mrs. Lotfi, when will you come stay with us? Everyone always wanted her to come stay with them.

Anyway.

She loved to come home after having taken the bus, and to tell us whether the driver was any good or not, or whether she got one over on him.

What do I mean?

She'd see who she could give 10 cents to for a bus trip. As far as she was concerned, that's what the trip was worth, and she wasn't gonna pay a penny more.

Another time, she, my dad, and I went fishing at a local lake.

These two Mexican boys, maybe around my age -- I'm guessing 8 or 10 -- had better luck than I had (they said they used peanut butter on the hook -- don't ask me how that works), and caught a pretty big fish. I want to say it was a catfish, but I don't remember.

What I do remember is the look of the pride on those boys' faces.

My grandma was sitting back watching everything, not understanding a word, but told me, "Tell them I want that fish."

I was like, Grandma, I can't do that.

I think she gave me the Grandma Glare and was like, I'm telling you, go tell them I want that fish.

I couldn't.

So, by means of gesture and Grandma Gravity, she indicated to the boys that she wanted to buy the fish. I think she gave them a dollar or two.

You could tell they were a little crestfallen -- pride goeth before a fall, I think? -- and disappointed to get that deal, but -- I think they, too, came from a culture where you don't back-talk Big Mama.

Here, again, though you might not feel it in the reading -- another long pause.

This feels like a good stopping-point.

Well, actually -- you know, I've learned always to follow the flow.

I think of the Zen story of the butcher and his knife.

When it came to carving oxen, a normal butcher might whet, or even change, his knife every few months. A middling butcher, once every year or two. But the master butcher (I'm not talking Vincent Price from Ten Commandments, but someone far nobler) said, I've had the same knife for 30 years, I've never sharpened it, and it glides as effortlessly as ever through things. I just follow the contours of the ox, it's like a dance where my feet never touch the floor, and at the end -- the whole thing falls from the bones with nary a nick.

Still -- when I sketched this portrait in thought, one phrase kept coming back to me. Maybe you'll say this spoils the masterpiece, but I'd be remiss if I left this out.

My grandma, whom I despised for a brief while, in whom I saw no depth, said many things that, as I've aged and as I've gone deeper and deeper into my Qigong practice, I now see to be perfect wisdom.

I said I'm going deeper, but I haven't plumbed the depths of this one yet.

It's been coming to me a lot lately, and -- dare I say, I'm finding it's one of the most profound truths I've ever heard -- or, more importantly, experienced.

Do you know what she said?

I told you she wasn't educated -- she could barely read. On top of that, she was an old-time farm girl with a country accent, and she said this to me in her sing-songy, "Now, I'm teaching you a lesson, Honey," tone.

She said, "Sa'i-aat o bokon -- do'AAT ham bokon."

That's how I remember it, anyway.

Do you know what it means?

Make your efforts, OK? But say your prayers, too.

Or, you do your part, and God will do his -- but not if you don't do your part.

The proof is in the pudding:

12 April 2022